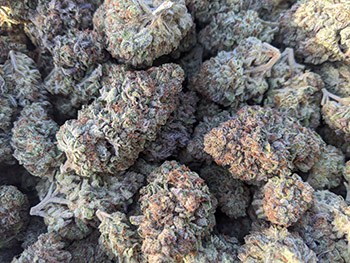

Courtesy of Sol 7 Farms

When Amber Speckman started cultivating cannabis nearly a decade ago in Northern California, it was consistent with her passion to help people.

Speckman’s background includes a master’s degree in marketing and business, but spending two years helping to nurse her mother, who died of cancer, motivated her to go back to school and earn degrees in holistic health and nutrition. Speckman then moved out of the country and opened a holistic health and wellness center, which she ran for seven years.

But when her father’s health began to decline, she moved back home to take care of him and had a son at the time. To meet the financial needs of her family, Speckman put 25 cannabis plants in the ground, which she said was the legal number she could cultivate in 2013 with her medical license.

“It was consistent with my passion to help people,” she said. “I’ve always loved natural medicine. And it was a way that I could work from home, take care of my family and then also provide natural health and medicine to people who needed it. So, that’s how I started cultivation about a decade ago.”

Courtesy of Sol 7 Farms

The owner of Sol 7 Farms, Speckman’s family operation now has seven team members who cultivate 14,000 square feet of cannabis and produce high-end flower from the Emerald Triangle.

While Speckman doesn’t consider herself a legacy farmer, she’s passionate about keeping smaller farms in business, she said. Working toward that objective, she’s one of seven farm owners in the Emerald Triangle—including Humboldt, Mendocino and Trinity counties—who joined forces to launch Cannavia, a cannabis company that is legally a corporation but aims to function in the spirit of a cooperative.

Founded by co-CEOs Michael Horner and Chris Leonard in 2019, Cannavia is vertically integrated and fully owned by its farmer and producer members. It’s pillared to help smaller farms own their brands, build equity and retain the legacy culture that helped create the cannabis space in the first place, Horner said. Furthermore, Cannavia is designed to help small-scale farmers in California maintain their independence and financial stability, he said.

Under the Cannavia brand, farmers collaborate to grow predetermined cultivars and harvest enough product to not only secure shelf space in retailers but produce consistent yields to keep that shelf space. All the initial fundraising, starting with the seed money, comes from the family farmers, who buy into the company to receive brand equity and shares in the corporation. While the farmers focus on growing, Horner and Leonard, who have entrepreneurial shares in the company, handle corporate structures like branding and distribution.

Through that collaborative membership in Cannavia, Northern California farmers can focus almost all of their efforts into growing quality and consistent products while still maintaining some sense of ownership and control in a vertically integrated marketplace, Speckman said.

Courtesy of Sol 7 Farms

Although Speckman has a background in business—as do other founding members of Cannavia—she said she does not have time to be shopping her product around.

“I think for smaller farms, in order to be effective and functional, they need to really work together,” Speckman said. “We all know the necessity of working together to not just succeed and thrive, but to actually just survive.”

Geared toward operating in the spirt of a cooperative, Cannavia’s farmers have had to concede some of their individual practices and wishes, such as cultivars they grow under the brand name, in order to achieve the same quality product, Speckman said. Consistency in that product, even down to the size of the flower nuggets they package, can be a determining factor in the Cannavia brand success, she added.

Preserving the Fabric of the Industry

Courtesy of Cannavia

Horner found his roots in the cannabis industry in 2008, when he left his corporate job to start a consulting firm to help entrepreneurs and businesspeople create “legitimate” businesses out of what they had been doing for years as a labor of love, he said.

“I’ve always kind of rooted for the underdog and wanted to help the little guy,” he said. “At the end of the day, a group of small family farms are stronger than they can ever be on their own.”

While an uptick in consolations among multistate operators continue grab headlines as the space matures, the cannabis industry historically has been very much “mom and pop” with a rebellious culture at its core, Leonard said.

“I used to always tell people, ‘Hey, it’s the coolest industry in the world,’ when I was going to the funkiest little pockets of California to meet these shop owners and operators that were servicing the grow community,” he said. “So, just historically, it’s the people, it’s the character, like, the fabric that has held all this together. And somebody said this at one of the shows a long time ago, … ‘Look, none of us are rocket scientists, but it’s our soul, it’s our passion,’ and that’s the glue that stitches this whole fabric together. That’s what’s kept me in the industry for a long time.”

Cannavia co-founder Leonard entered the cannabis space with a friend, manufacturing grow lights in the mid-2000s, but his specialty is on the branding and marketing side of the industry. In 2015, he co-founded Cannaverse Solutions, which is built to arm heritage farmers with the tools they would need to compete in the marketplace, he said.

“What you learn really quick is it’s near impossible for a single farm to go out in the marketplace in California and make a real big impact,” Leonard said. “Unless you’ve got a lot of capital behind you, unless you’ve got a bunch of business-savvy people, you’ve got a legal team—you really need to have a lot to compete in this marketplace just due to the size and because it’s so overregulated.”

RELATED: California’s Cannabis Industry Marred by Limited Supply Chain and Heavy Tax Burden

A Collective Stake

As state-by-state markets continue to grow, those already with a footprint in the sector are poised to go bigger while potential major players outside the cannabis industry are looking for a way in, said Jared Schwass, a licensed attorney in California who is an associate in the Fox Rothschild law firm’s Cannabis Law Practice Group.

Courtesy of Sol 7 Farms

In February—three months before Trulieve Cannabis Corp., a licensed operator in California, announced its $2.1-billion definitive arrangement to acquire Harvest Health and Recreation Inc.—Schwass told Cannabis Business Times that consolidation in the California market was ripe, partly because of its abundance of independent operators.

“The small farmers up in Northern California are struggling,” he said about remaining competitive in a maturing market that continues to consolidate. “But I think through struggle comes perseverance. I think there is something to be said about these small farms and these small kind of craft brands that there still is a market for them, and there will continue to be a market for them.”

At first, there were some growing pains associated with seven established farmers developing one standard operating procedure under the Cannavia brand, Speckman said.

“It’s like herding cats. It’s not as simple as it sounds,” she said. “We’ve all been individual mavericks for so long, and then all of a sudden we all have to work together. It’s not that it’s been extremely hard; it’s just, you have to be willing to adapt.”

But the payoff could be huge, Horner said.

While Cannavia launched with seven founding farmers, the company is in the process of adding 12 more farms to its controlling membership this year, Horner said. The goal is to expand to 40 acres of production, which would make Cannavia competitive with some of the largest cultivators in the state, he said.

Inspired by cooperatives like the Tillamook County Creamery Association headquartered in Oregon—a 100-plus-year-old company that sells dairy products like cheese and ice cream under the nationwide “Tillamook” brand name—Cannavia is working toward securing more shelf space in top-line retailers, Horner said.

“We want to be that for the cannabis industry,” he said, referencing Tillamook. “So, that sort of brand equity is one of the big reasons to be involved with a corporation like ours. Cannavia will build the brand and give farmers the brand equity piece that they need [in order] to hold value in their product and not be subject to commodity spot-market pricing season after season. You know, it allows the small family farmer to do what he [or she] wants to do—farm.”

Coming from different backgrounds to steer the same ship, Cannavia farmers have also built a community to exchange knowledge from throughout the Emerald Triangle, Leonard said. Each farm owner controls the direction of the company through his or her seat on Cannavia’s board of directors.

Sometimes corporate interests can overtake the cannabis culture in a company, which in turn could jeopardize the recipe for success, Leonard said.

“We’re trying to blend our skillset with the heritage part that the farms offer and offer the best possible framework for Cannavia to thrive in the marketplace,” he said. “We need to be able to pool resources, pool our collective knowledge, or collective grit so to speak, and offer a way where there’s a clear pathway forward for these small heritage farms to exist in the marketplace where they’re not just a commodity farmer.”

Functioning as the spirit of a cooperative does take a considerable amount of trust and camaraderie that is not always ubiquitous in the cannabis industry, which historically can be guarded with farmers attached to their individual craft, Speckman said.

Having a collective stake in the marketplace has bridged those divides at Cannavia, she said.

“It’s incredibly beneficial because none of us want to sell out and be corporate and be huge,” Speckman said. “We all want to maintain some semblance of integrity in that small-craft feel, but in order to survive, we really need to work together [and] pool resources to pull it off.”